“The term ‘weekend’ is pretty hollow nowadays, because the week doesn’t really end,” says Sander Ettema, late on a Saturday morning, as we chat about his latest book, Friends In Many Places. He’s got a day off (he works producing vector graphics for various websites and illustrations for Vice NL,) but he’s using it to work on yet another book. He hasn’t even had a coffee yet.

It’s hard to keep up with Ettema, a self-taught illustrator who jumped straight into freelance work after a desultory period working as “a garbageman, a metal worker, in a storage freezer. Shit jobs, and doing illustration on the side.” His phenomenal productivity comes from a love for what he does, but it’s also driven by some deep-seated anxieties and obsessions. “I tend to get lost in this mania where I feel like there’s always more to be experienced, I go over my own borders. I never have a clear line where the one thing stops and the other begins.”

Friends In Many Places is a comic about facing up to your fears—self-worth, work-life balance, imposter syndrome, or moths (“I can’t be in a room with roaches or moths,” he says)—issues that many people working in creative industries can empathize with, and learning to channel them into work. The book began as a diary during a particularly dry patch of freelance work, and the five acts of the story embody the different roles or moods he found himself taking on as a coping strategy. “I quickly penned down some ideas whenever they would arise and basically would work from page to page. I think it was more important that I got things straight in my own head, and the comic is really the residue of that.

“It was mostly me trying to understand my emotions and thoughts, because they were very heavy, convoluted and irregular. I think that’s reflected in the visual language too.” His visual vocabulary is enormous, ranging from the animatronics of the Henson studio to the postmodern architecture of the Flintstones movie, Martin Scorsese’s noir homage After Hours, the Cowboy Henk, and Little Nemo comics, and video games such as Earthbound and A Link to the Past.

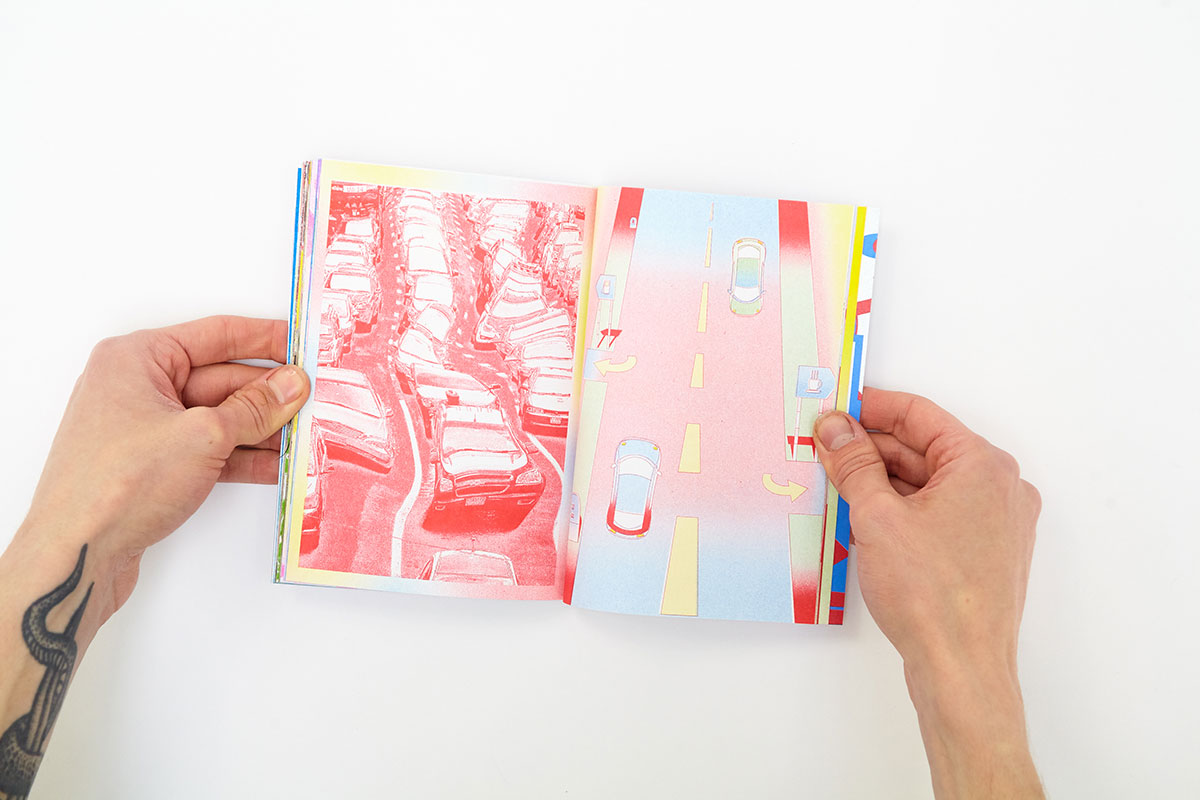

The mixed-up result is a loud, brash, bold example of the king of ugly design that everyone hates to love. His cast of characters—goodies and baddies, oppressive demons and relentless bullies—speak in catchphrases drawn straight from the “zany cinema” he admires. To help this intensely personal comic speaks to people beyond himself, Ettema found it useful to distance himself by turning to metaphor and abstraction. He uses the recognizable imagery of clip art, instruction leaflets, browser popups, and desktop icons to create something approaching an “instantly readable symbolic language.”

Still, it’s difficult to read, only because Ettema’s is a fundamentally unforgiving world. His nameless comic stand-in runs incessantly from scene to scene, fleeing from Dungeons & Dragons castles to the apartment of an ultra-masculine bro, waking up to find himself a rat in a laboratory maze, before being forced into a socially uncomfortable self-reckoning. “There’s no clear resolution,” he says, “if there’s any it’s that there’s no point in hiding the way you feel, because it will catch up with you in the end. You need to confront yourself.”

Has Ettema taken this on board when dealing with his own anxieties and phobias? “I think I got more aware of the way things work now for me, I don’t see the work as the ultimate goal any more,” he says. “I’ve still got that itch though. As far as being able to maintain presence and be in the here and now, that’s the hardest thing for me. There’s not always the opportunity to take a few steps back.” But with the book being printed as we chat, surely he’s glad to sit back and rest? “Surprisingly it just fed a new hunger, a new amazement. Like, ‘if I could have a beefy zine out in six months surely I could do another smaller one quicker?’ It’s this constant cycle.”