There’s a lot of power inherent in the language we use and how we choose to use it. It’s a fact long acknowledged by the women’s movement, which in the 1970s introduced terminology around domestic violence. In recent years, terms like mansplaining (thank you, Rebecca Solnit) and man-spreading have popped up, not just to describe some undeniably annoying phenomena, but also to bring to light a historic imbalance in gendered terms.

For artist and software engineer Omayeli Arenyeka, the word “fuckboy” was the neologism that brought this imbalance into focus. “I used the word while talking to friends, and it made me wonder why there are so many words for women who are sexual, and this one for men that has come up pretty recently,” she says. “I wanted to be able to point to something that says there is an imbalance, and to explore what language has to say about the society we live in.”

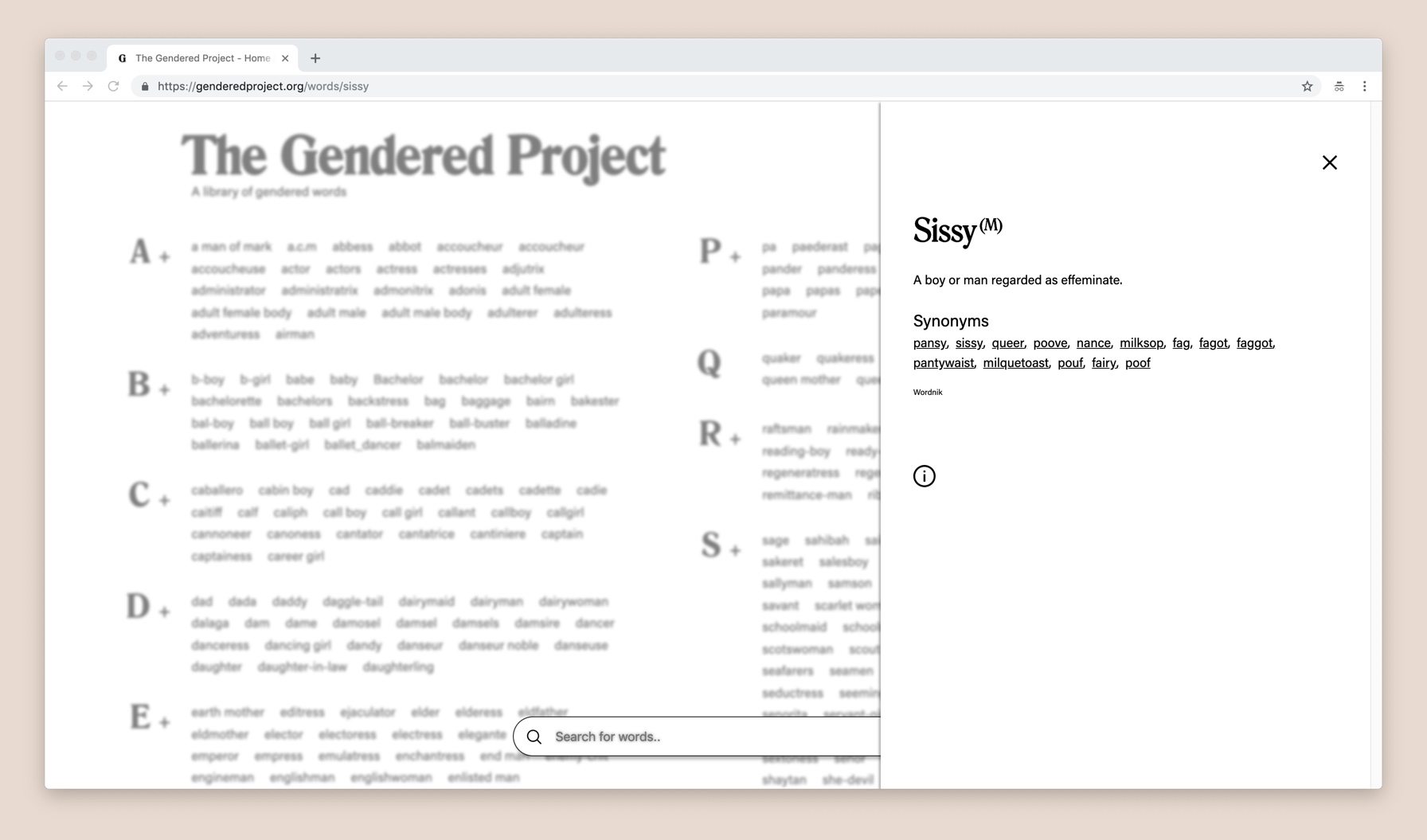

From those humble beginnings The Gendered Project sprung, an unfussy, considered website that catalogues 2,200 gendered terms, and growing. Arenyeka wrote code for collecting and filtering English language words that are gendered—or mention either male or female in their definition. Her friend and collaborator on the project, Sean Catangui, designed the site. Deceptively simple in scope and presentation, the project is a neat approach to the often slippery topic of semantics, pulling in actual data to support the discussion around the biases built into certain sexualized words.

“I think the potential for technology in this area of research is really for automation,” says Arenyeka, who began the project after doing some reading on gender and language usage (which she’s kindly compiled here). One project she became especially interested in was Julia Stanley’s 1977 paper “The Prostitute: Paradigmatic Woman,” in which she found 220 terms referring to “women as prostitutes” compared to 20 for men in the Oxford English dictionary. This being the 1970s, “she went through the dictionary herself, which is wild and shows her dedication,” says Arenyeka. But 2019, this type of data collection could be done much faster, and allow for a broader scope.

To collect the data, Arenyeka started with an initial dataset using the API of the online dictionary Wordnik. She wrote code for a reverse dictionary search to find all words that contained terms like “women,” “men,” “he,” “she,” “male,” “female,” in either the word itself or the definition. After deciding to begin the project with nouns only, Arenyeka used a program called NLTK (or Natural Language Toolkit, which builds Python programs for language sets) to scrape the list for non-nouns (and then again for categories like “clothing” or “animals,” which include lots of gendered words but didn’t fit the project’s purpose).

The last test checked to see if the word before “man” or “woman” in the definition was the object of a preposition, effectively getting rid of the names of people (i.e. the proper noun Peter, with the definition [a fisherman] of Galilee and one of the 12 disciples, would be scraped). Arenyeka then created an API to hold the data, and she and Catangui went through themselves to filter any remaining words to make sure the meaning aligned with the project—a process she’s hoping to soon make crowdsourced.

The result of this process is a website listing words like oldtimer (M), mistress (F), damsel (F), ladies’ man (M), man-eater (F), and nance (M). A lady can be both a ball-breaker and a ball-buster, particularly if she’s a temptress, enchantress, vamp, nymph, vindicatress, or “jill-flirt.” Then there are those “golf widows,” the women who lose their men morning to late afternoon to the golf course, a group native to the suburbs. With words listed alphabetically, comparing male-to-female (or vice versa) equivalents takes a bit of legwork for the visitor; to find the “fuckboy” to your “slut,” for example, would require venturing out of the respective categories and making the association on your own.

If at first glance the site appears “undesigned,” it doesn’t identify as such. Several subtle design elements make the growing library of words more servicable—a plus sign brings up more words in the category, and clicking on a word prompts a pop up definition to slide in from the right side. Even Catangui’s typeface choices were meant to subtly show that there’s often more to things are than meets the eye. The display font, Romana, looks traditional, with “strong cuts that hint at a sturdy, masculine font, but subtle smoothed corners make its mood more ambiguous,” he says. Acumin, used for the text, looks at first to be the Helvetica it’s based on, but with several clever improvements that come to light on closer examination.

For now, The Gendered Project is meant to simply provide a resource for gendered words, whether for academic research or for simple curiosity, and hopefully along the way demonstrate that language usage is never merely neutral.

“On an individual level, I think it’s helpful to be able to look at the data and think about the language we use more critically,” says Arenyeka. “After seeing the project, a friend of mine said that she realized when she called her partner a ‘drama queen’ it was gendered—there was no real equivalent for males. When you use the word ‘sissy’ it creates boundaries around what a man should be.

“The idea is to be able to look at the language we use, and consider, ‘What ideas are we communicating?’”