Frederick Hammersley is best known as an abstract painter. A “hard-edge” painter, more precisely. The Hard-edge painters of the ’60s and ’70s—artists like Ellsworth Kelly, Frank Stella, and Kenneth Noland—were marked by a certain aesthetic: geometric shapes, vibrant colors, and great attention to the surface and order of the canvas.

Hammersley’s paintings were similar, but different. They embraced organic compositions of shape and color. Sometimes they featured more linear (almost mechanical) geometrical shapes. This breadth of styles is fitting. Throughout his life, Hammersley explored different mediums as way to rethink ideas about process and image making.

For example, during WWII, Hammersley served as graphic designer in the U.S. Army Signals Corps and Infantry. He continued working in graphic design well into the ’60s making illustrated advertisements and magazine covers. He dabbled in lithographs, experimenting in abstraction, shape, and color, and sculpted in clay. What may (or may not) come as surprise for those familiar with Hammersley’s work, is that for a very brief moment in his life, he created a series graphic images using one of the more unlikely tools in his era: the computer.

In 1968, Hammersley moved from Los Angeles to Albuquerque to take a teaching position at the University of New Mexico. It was there that he met Richard Williams, a computer engineer who wrote ART I, a computer program designed for artists with no computer background to make art. Hammersley took a workshop with Williams to learn the program, and was struck by both its endless possibilities and inherent limitations. More importantly, Hammersley was continuously fascinated by the difference between his own expectations of what printed image would look like and its final result.

They almost had the form of a Josef Albers color study, minus the colors.

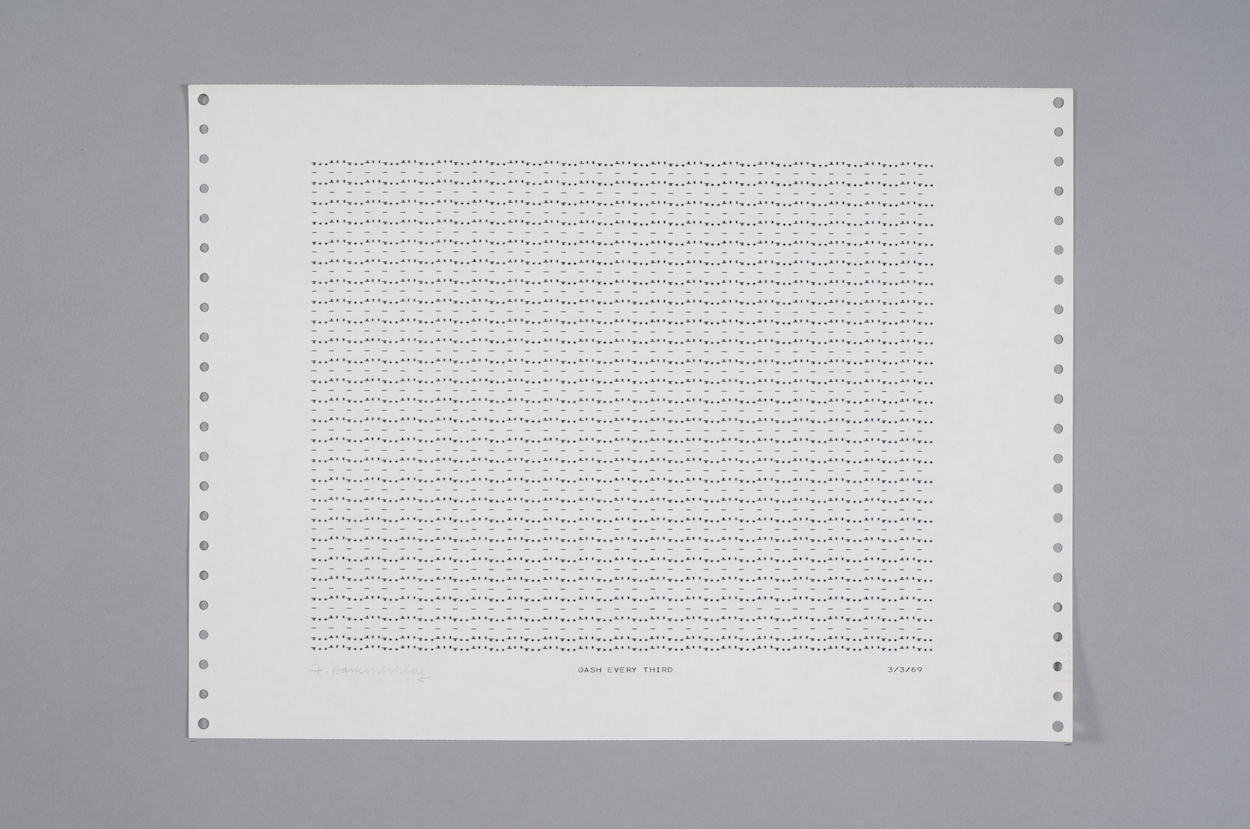

From 1969-70, Hammersley created approximately 400 different computer drawings, 72 of which would become part of the formal set entitled “Computer Drawings.” The resulting images were stark, two-dimensional, and rudimentary, yet they were graphically complex. Some resembled certain motifs in the artist’s earlier paintings, albeit more machine-like, with curves and patterns. Others almost had the form of a Josef Albers color study (minus the colors). With the computer Hammersley was able to create geometric shapes like circles and squares, while also experimenting with shading and movement across the page (a technique achieved by printing on the same image twice).

For example, “Clairol (1969)” is a beautiful collection of dashes and parentheses that create a wave-like pattern that both recedes and jumps out of the picture. “Yo Yo Almost ..1 (1969),” is made up entirely of periods and apostrophes, showcasing a series of undulating lines that together gives the impression of a waving flag. Many other drawings in the series are much more complex, but reminiscent in all of them is a deliberate and convincing use of negative space—something that would resurface in some of Hammersley’s subsequent paintings.

Hammersley’s computer-generated drawings are among the early explorations of this niche art form. They coincidentally came at a time where the artist had felt uninspired by painting. In an essay first published in 1969 in Leonardo entitled “My First Experience with Computer Drawings,” Hammersley candidly wrote: “… I had painted myself out, so I welcomed this new experience.” And although Hammersley goes on to liken the experience of coding to that of painting, the process of making computer drawings couldn’t have been more different.

Hammersley was struck by the computer’s endless possibilities and inherent limitations.

The limitations of drawing with a computer were astounding. For starters, Hammersley’s drawings were defined by an alphanumeric set of characters: “the alphabet, 10 numerals, and 11 symbols, such as periods, dashes, slashes, etc.,” as he explained it. The images were then limited to 150 characters across the page horizontally and 50 characters vertically (the resulting image size being 8.25” x 10.5” on an 11” x 14.75” sheet of paper). Hammersley would then write out the images by hand, using this prescribed lexicon, and carefully transfer that information onto a small pink punch card that was fed into IBM 360 computer (think giant hunk of machinery that would take up an entire room) and later printed using an IBM 1403 line printer.

As Elizabeth East, director of L.A. Louver and curator of the 2013 exhibition “Frederick Hammersley: The Computer Drawings 1969,” recently told me: “In order to instruct the computer through these punched cards, they would have been administered by the engineer who knew how to work the machine. The computer wasn’t just making drawings all day, so Frederick would deliver something to the engineer and later in the day he would come back and pick up the printouts.”

After a year of coding and print-outs Hammersley decided to drop his graphically inspired computer renderings and venture back into painting. It’s not entirely clear why he stopped after such a short stint, but the speculation is that his brief foray into computer art had simply run its course. “He basically felt that he had done all he could with the medium, and some painting ideas began to creep back in, so he dropped the computer art and went back to painting,” said Patrick L. Frank, an art historian and scholar of Hammersley’s computer drawings. Nevertheless, Hammersley would go on to produce some of his most impressive works, including a series of lithographs heavily inspired by his computer drawings but with the addition of color, as well as his series of symmetrical black-and-white paintings in the early ’70s.

They are an outgrowth of the same ideas that I use, for the most part, in my paintings—a kind of marriage of opposites.

It seems that throughout his life and career, Hammersley was constantly battling between two separate aesthetics: one that was more gestural and intuitive but clouded by human imperfections (painting), and another that was automatic and exacting, yet shrouded with limitations and uncertainties (printmaking and computer design). Nonetheless, Hammersley was able to reconcile this tension. As he explained in his aforementioned essay: “As to the significance of these drawings I can say that they are an outgrowth of the same ideas that I use, for the most part, in my paintings—a kind of marriage of opposites.”

During his tenure as painter, Hammersley kept a series of “Painting Books.” The journals detailed every step of the painting process, from stretching the canvas to applying the coats of varnish. After “Computer Drawings,” it’s suspected that Hammersley’s “Painting Books” became more meticulous due to his experiences with Art I. As a result, Hammersley’s approach to painting, following his computer drawings, became obstinately obsessed with a rigorous process: one reliant on rules and constraints but also open to new discoveries.