OBEY. BUY. DO NOT QUESTION AUTHORITY. Black and white, block capital text—bleak reminders of the domineering capitalist doctrine that lurks behind billboards and magazines—are at the heart of John Carpenter’s 1988 cult classic They Live. The film is a text laden with this sort of graphic ephemera, once you spot it—pieces that drives the plot as much as wrestler-turned-actor “Rowdy” Roddy Piper’s hammy-leaning dialogue.

As anyone who’s seen it will know, there’s one piece of printed matter in particular that lies at the heart of the film, which is part schlocky sci-fi alien invasion, part searing critique of 1980s inequality, unemployment, fragile masculinity, and Reaganomics. That piece is a magazine, or to be more accurate, a whole rack of magazines. Once our central character, John Nada, has found a pair of sunglasses that let him see the subliminal messages of advertising and media in stark monochrome, glossy magazines full of glamor and promises start to show their true colors—which are not colors at all, but black and white messages that keep the people in their place and instruct them to “BUY” and “OBEY.”

The centrality of that piece caught the eye of author and graphic designer Craig Oldham around four years ago, and he had the idea of creating a series of publications based on such “hero props” (or props that mark a turning point either in plot, or in a character’s interior motivations or realizations). Having managed to get approval from John Carpenter’s team, he found a publisher in Rough Trade, who he’d worked with on the Editions series of books from different writers, musicians, and artists who produce work related to the counterculture.

“Nina [Hervé, Rough Trade Books co-founder] asked if I had any ideas for books, and I thought she’d laugh me out the pub on this, it’s such a mad fucking nerdy idea,” says Oldham. She didn’t, of course, and it began an 18-month scramble to design, write, collate, and release a book that both recreated the prop and augmented it with essays, imagery, comics, and artworks. They Live: A Visual and Cultural Awakening will be the first in a series of publications that take a similar approach to examining a film through the lens of a single prop (the next film is likely to be The Shining). “Once you spot one [such prop], you see them in every film,” says Oldham. “The criteria for every selection is that they have to play a pivotal role.”

“I thought I’d be laughed out the pub on this, it’s such a mad fucking nerdy idea”

The book features contributions from Shepard Fairey (synonymous with the OBEY graphic, of course) and artists and collectives Brandalism, Jenny Holzer, Barbara Kruger, and the Guerrilla Girls; as well as essays by musician John Grant and philosopher Slavoj Zizek. The 1963 short story that Carpenter’s film is based on, Ray Nelson’s Eight O’Clock in the Morning, is printed in full; as its comic adaptation by Ren & Stimpy’s Bill Wray. Carpenter himself has penned the foreword and Oldham has written a number of essays.

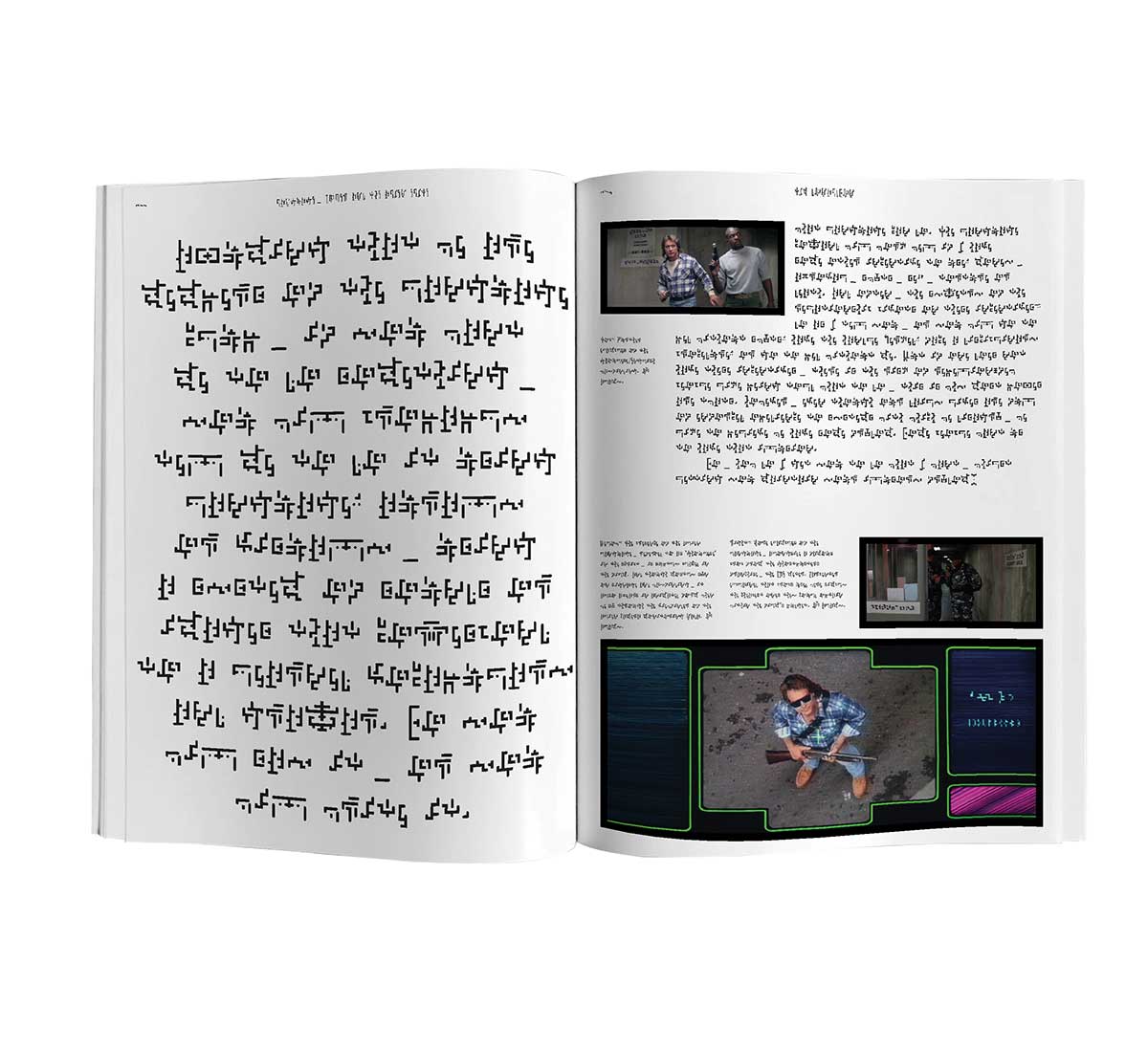

Design-wise, the cover and first few spreads are direct facsimiles of the original magazine prop, before the book moves into its richer manifestations of text and imagery exploring They Live in depth. “We were trying to honor the integrity of the film by taking those rich visual cues and littering them with a structure that’s more similar to a magazine than a book,” says Oldham. “Where a magazine can dance all over the place, you can’t do that as much with designing a book. I got round that by making the contributors’ pages white, and my pages black.” Some subtle and brilliant touches include the “ghost” UV text peppered throughout, and the bubblegum scented pages—a reference to a line from one infamous scene: “I have come here to chew bubblegum and kick ass…and I’m all out of bubblegum.”

The typeface used throughout is, naturally, Albertus, which Carpenter uses for many of his credits and titles, including Escape From New York, Prince of Darkness, Escape from L.A., as well as They Live. Oldham also worked with typographer Timothy Donaldson to develop the Formaldehyde-face “alien” typeface, a series of seemingly illegible glyphs seen in the film as the aliens’ text.

While Oldham was unable to see an original copy of the prop—such things have largely been destroyed—he did speak to Jim Danforth, who worked on the matte paintings used in the film for the pivotal scene in which Nada first uses the glasses and sees what the billboards are really saying. “It was a bit like archaeology to dig through everything,” says Oldham. “I got to see the original press kits and first releases of the film posters. Other stuff, like old magazines and books, I had to track down and buy myself.”

“I love how film draws on culture and has its own impact, as books can have.”

The idea of creating what’s essentially a book of film criticism and commentary that’s so entrenched in the movie itself feels akin to the huge Time Out-ish wave of “immersive” experiences we’re seeing at the moment, with the likes of Secret Cinema in London and Sleep No More in New York. People no longer just want to be passive spectators, but active participants in the plot itself.

“We didn’t want to produce something that was the exact replica [of the prop], but something that played out through more traditional means,” says Oldham. “Take the action figure boom. That came from people wanting to have their own environments from films, and that evolved into a culture where we can buy Julia Roberts’ dress from Pretty Woman on ASOS or something, and Bubba Gump Shrimp restaurants.

But I wanted this to be direct: I love how film draws on culture and has its own impact, as books can have. I want the book to have an impact, using They Live as a starting point. It’s full of other disciplines and sources that give a rich experience and connects those dots; not just through street art and music, but exploring conceptual art, gender, politics, homelessness—those all run through the film.”

What’s interesting about the book is its deft management of the tricky balancing act between prop replica and considered commentary. The tone of voice eschews impenetrable film or art theory in favor of a richly illustrated, clear delineation of the themes in They Live—ones that are chillingly relevant today. It’s not hard to see the parallels between the “gulf between the underclass and the ruling class,” as Oldham puts it, in the film and in today’s world. Or the racial tensions, or the language of Republican slogans. “Let’s Make America Great Again” was of course used in Reagan’s successful 1980 presidential campaign, and you don’t need us to point out where that’s come back 30-odd years later.

“For many reasons I wanted to avoid the kind of vernacular that might alienate people,” says Oldham. “They Live handles big themes—a lot of them are explicit, like the politics and consumerism and media things, but others are hidden in the subtext, and it’s ok for someone to have their own reading. I used the film to get my point of view across, the whole left wing thing, but there’s also things no one’s discussed, like the gender imbalance. Foster’s character [Holly Thompson] is often seen as a useless love interest, but there’s more to it than that, and Carpenter spoke a lot about being fed up with that ‘invincible man’ thing, so I wanted to talk about that.”

The alignment with the social and political issues between then and now, as well as those discussions around fragile and/or “toxic” masculinity make it seem a perfect time to release this investigation of They Live in those contexts. “With cult films there’s often a community that will resurface them and they’ll suddenly become relevant again. Films always manage to talk about issues that people might not otherwise discuss, too: take the boom in vampire movies in the late ’80s at the same time as the Aids crisis for instance,” says Oldham.

“You can’t ignore that it’s a good time to reappraise the film.”